If you live in Miami, you know about Junkanoo and its bright-colored costumes, brass-led parades and calypso rhythms. You know that this festive occasion represents the string of islands just 53 miles east of Miami. But that may be all you know about the Bahamas.

If you live in Miami, you know about Junkanoo and its bright-colored costumes, brass-led parades and calypso rhythms. You know that this festive occasion represents the string of islands just 53 miles east of Miami. But that may be all you know about the Bahamas.

“The Bahamian community here in South Florida is a shadow community. Bahamians behave very much like the Canadians among Americans. They sort of blend in with the African Americans and are not clannish at all,” said Judith Missick, a Bahamian who has been living in Miami for over 30 years.

She may be right because – outside of their annual Goombay Festival (which has now been re-branded by new organizers as Miami Bahamas Junkanoo Festival) - Bahamians don’t seem to have a very formidable or distinct identity in South Florida.

“Even the food is not much different than what we eat here in America besides the conch,” said Missick.

Macaroni and cheese, potato salad and cole slaw, popular Bahamian side dishes, can also be found packaged in the deli section of a local Publix then set on a picnic table for any American family to enjoy.

Missick attributes her community’s assimilation to two factors: the islands’ proximity to the United States and how long Bahamians have been immigrating to Miami.

Arriving in the late nineteenth century, Bahamians were among the first Caribbean islanders in the United States. Many came to Key West to labor in fishing, sponging, and turtling and others migrated to work at the Peacock Inn on Biscayne Bay, establishing the Village West neighborhood in Coconut Grove. The community was the first black settlement in South Florida.

Raymond Mohl wrote in his 1987 article “Black Immigrants: Bahamians in Early Twentieth-Century Miami” for the Florida Historical Quarterly that Miami was a ghost town when it was incorporated in 1896, with only a few hundred people living there.

“By 1900, the population had increased to 1,681, including a sizable number of black immigrants from the Bahamas,” he wrote.

Twenty years later, Black islanders - almost all Bahamians - comprised 52 percent of all of Miami’s Blacks and 16.3 percent of the entire city’s population.

At the turn of the 21st century, though, native Bahamians comprised only 1.5 percent of the Black population in Miami-Dade county while Jamaicans were at 6.7 and Haitians were at 14.8 percent.

Why the drop off? There are a few explanations.

As the economic situation for The Bahamas improved due to a stabilizing and growing tourism industry, Bahamians returned to their homeland while the economies of its third-world neighbors like Jamaica, Haiti and the Dominican Republic declined, prompting their citizens to immigrate to the United States at a faster rate.

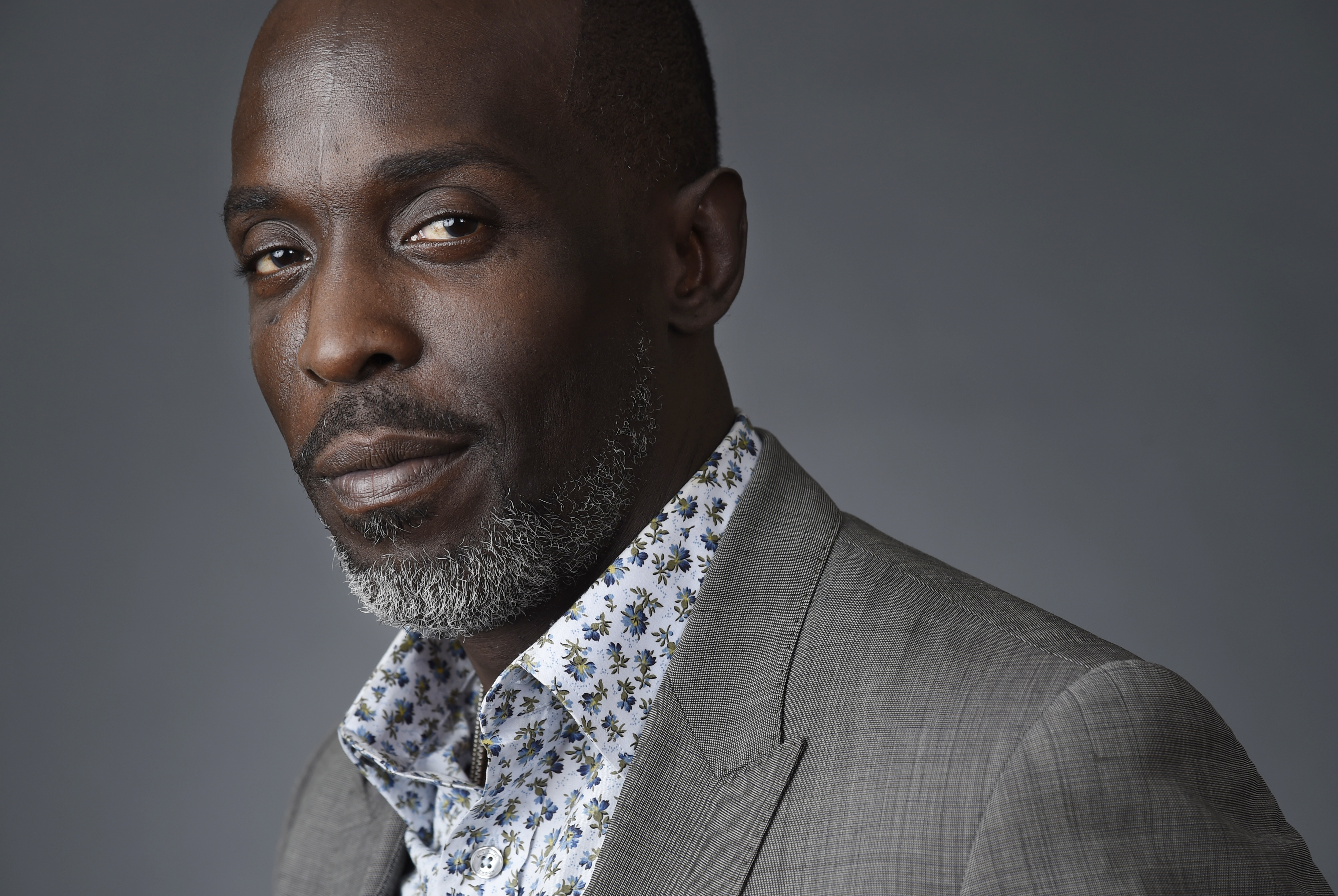

Many Bahamians began to marry Americans, so second and third generation Bahamians like actress Roxie Roker and actor Michael K. Williams would take on an American identity.

Many Bahamians began to marry Americans, so second and third generation Bahamians like actress Roxie Roker and actor Michael K. Williams would take on an American identity.

Lastly, Bahamian women made conscious decisions to make the quick trip to Miami while pregnant, stay for a few months and give birth to their children on American soil, making them American citizens.

Andrew Brown, a retired Miami-Dade county physical education teacher, says that his mother was one who gave birth to her first seven children in Miami. She later moved back home, fell in love with another man and had Brown and his three sisters in Nassau, Bahamas.

Brown was 12 when he moved to Miami with his three sisters. He was a rambunctious child and a gifted athlete, but he remembers that segregation was palpable in 1958 Miami-Dade county.

“My name was Andrew Marcian Kenneth but I used to be called Marcian in the Bahamas. A White customs officer took the name away from me and registered me as Andrew Kenneth because he said my name was too long. He didn’t even give me a choice,” said Brown. “I hated the United States for doing that to me.”

After his name change, Brown experienced culture shocks within his new segregated city that he had never experienced in The Bahamas. Experiences like standing at the outdoor window of McCrory’s ordering corndogs, drinking from a Colored water fountain and using a Colored restroom were all new for him.

It wasn’t until civil rights activists like Father Theodore Gibson, Reverend Edward Rollington Ferguson and others banded together to fight for integration that things began to look more like the country that Brown had left behind.

Rev. Ferguson, a Bahamian minister and the founder of Beulah Missionary Baptist Church, 3795 Floyd Avenue, in Coconut Grove, enlisted his newly immigrated children to be a force of change in their new city.

“I remember riding the metro bus with them and my father told me to sit in the front seat and that if they told me to move, ‘Don’t move,’” said Zelma Ferguson Siplin, the now 76-year-old daughter of the late Rev. Ferguson, who has been living in Miami since 1972.

Her siblings were also the first Black children to attend Palmetto Middle and Senior High schools.

“As Bahamians, my dad taught us to have respect for ourselves and respect for others,” said Siplin. “He told us that people may laugh at us for what we’re doing but we would have the last laugh. And whoever laughs last, laughs the longest.”

As pillars of the Coconut Grove neighborhood, her family had been active participants in the Miami Bahamas Goombay Festival since its inception in 1976. Many viewed it as an opportunity for Bahamians to share the rich history of their people starting from the Caribbean and extending to Florida.

Ziplin said her mother was known as Bahama Mama at the festival for her authentic Bahamian treats like boiled fish, conch fritters, pigeon peas and rice and guava duff.

However, Ziplin says that once festival organizers put a divider down Grand Avenue, it affected the turnout.

“Then, they moved it to Peacock Park and it went down to nothing. They also started to go up on rent and vendors couldn’t afford it,” she said.

“Then, they moved it to Peacock Park and it went down to nothing. They also started to go up on rent and vendors couldn’t afford it,” she said.

With the new management in 2015 and the support of the Bahamas Consulate General and the city of Miami, bands like Bahamas Junkanoo Revue say that the festival is better organized and is actually now offering fair compensation to the talent.

“Bahamas uses Junkanoo as their number one ambassador to reach out to everyone else in the world. We’ve been featured at the MLK parade, Calle Ocho, Miami Carnval across the country. We tend to dominate things when we show up,” said Langston Longley, the founder of the 26-year-old performance group.

Longley and his 25-member crew use their Junkanoo artform as a method to reach young people in Miami-Dade county, inspiring teenagers –who aren’t exclusively Bahamian – to begin playing music, to receive payment for performances and apply their brass and drum instrument knowledge at school.

“I tell the students that it’s better to have a music addiction or a sports addiction than a drug addiction,” said Longley. “We want to make Junkanoo an addiction for these kids.”

For people like Longley, Junkanoo runs in their veins. They have been building costumes and playing cow bells since they were pre-teens on Bay Street parades in Nassau.

Junkanoo is now a year-round festival attraction in The Bahamas and the natives have always been particularly aware of its nation’s power to draw tourists from around the world.

“As Bahamians, we love everybody; the first thing you see when you meet us is a big old grin. We were never taught to dislike anybody because the very economic stability of our country is based on us being hospitable,” said Missick, who serves as the Missions Director at Open Bible Community Church, 2610 NW 119th Street, in Miami.

While her church is home to a predominantly Jamaican population, Missick says she feels right at home.

“I feel comfortable in my own skin. I don’t ever feel singled out. I know I am there to add a special flavor,” she said.

Mable Ferguson Smith, who moved to Miami when she was 11, says she became fast friends with American children at Miami Edison Middle School and even invited them to her home in Bimini, Bahamas on Christmas holiday break.

Smith maintains that even though she has a lot of American friends, she notices that some Blacks in America suffer from an inferiority complex that is completely non-existent where she’s from.

“In the Bahamas, Blacks are in charge. I didn’t have Black and White issues. I never had that ‘not enough’ problem,” she said. “I never thought that a White man was better than me or they could advance further than me.”

In fact, Smith recalls that growing up in Bimini, everyone had their own entrepreneurial endeavors like fishing, running restaurants or creating straw crafts; therefore, its citizens had no room for an inferiority complex.

“When the White people would come, they had a sense of ‘I want to get along with you.’ They didn’t come to my country for them to say, ‘You’re my servant,’” she said.

This mentality is something that most Bahamians carry over to the United States; however, Missick says that she sympathizes with the struggles of Black Americans because all Blacks are lumped together in the U.S.

Years ago, when Missick and her husband were first searching for apartments in North Miami, they would be approved for the apartments on the phone but when they would arrive, the landlord would renege.

“One time, my husband was even thrown against a car because he was the wrong color looking for work in the neighborhood Key Biscayne,” she said. “This is why I feel the pain of Black Americans. If I’m being treated like them, why would I see myself as different?”

She claims that sometimes her White colleagues would make comments about Blacks without thinking that Missick would be offended.

“They say, ‘No, Judy, you’re Bahamian,’ but I’m still offended because I’m Black,” she said.

Brown claims, however, that many Black American youngsters create unnecessary mayhem for themselves at the hands of law enforcement officers in South Florida.

“I was a bad-behind boy from Nassau and I spent time observing people and observing nature,” said Brown. “Man is the only one who kills himself.”

While teaching at Little River Elementary for 14 years, he would admonish his Black and Haitian American students to “keep a policeman, a policeman; don’t make him into a killer. Say yes, sir and no, sir. Respect him and he’ll respect you.”

Longley, who is a realtor by day, says that race and culture is definitely a factor in South Florida real estate, even for a Bahamian.

“I was once post in an office in California Club, then in Hallandale Beach then in Aventura…when I got there, I knew right away that I had to find a new office,” he said, referring to the city in Northeast Miami-Dade with a 73 percent White population. “When you’re dealing with a lot of money, they may think you’re not as competent.”

Once he was transferred to the Miramar office where a large amount of inquiries were from the Caribbean community, Longley said he felt far more at home.

“You have to sell what you believe in and I had more knowledge of that community,” he said.

The Bahamian community may not be as tight-knit as other communities in South Florida, says Smith, but she knows that she – like many Bahamians- are always ready to give someone a helping hand.

“At work, if I saw that someone had potential, I tried to teach them what I know,” she said. “I always say, if you learn it, no one can take it from you. You can get a better job and take it with you.”

She also believes that the Bahamian imprint in South Florida may not look like that of the Cuban or Jamaican imprint because “the dream for most of those immigrants is to come here; they can’t go back home and make it. For a Bahamian, we know we can always go back home.”

Tiffani Knowles is the managing editor and founder of NEWD Magazine. Her hope is to become as "newd" as possible on a daily by embracing truth, authenticity and socio-spiritual awareness. She is bi-vocational as she is the owner of two businesses and a professor of Communication at Barry University in Miami, Florida. She is also the co-author of HOLA America: Guts, Grit, Grind and Further Traits in the Successful American Immigrant.

Tiffani Knowles is the managing editor and founder of NEWD Magazine. Her hope is to become as "newd" as possible on a daily by embracing truth, authenticity and socio-spiritual awareness. She is bi-vocational as she is the owner of two businesses and a professor of Communication at Barry University in Miami, Florida. She is also the co-author of HOLA America: Guts, Grit, Grind and Further Traits in the Successful American Immigrant.