They were known for years as the Haitian boat people of Miami-Dade. In Haiti, they bear the title of “diasporas”– a term used to describe Haitians who live abroad. And yet, the Haitians who settled in and around Miami-Dade county have done much in the last 40 years to both shake the stigma assigned to the impoverished refugees from the poorest country in the Western hemisphere and still maintain strong cultural ties to their homeland.

They have etched out a firm place as the second largest immigrant group in the region, just after the Cuban immigrants – who share a similar refugee history.

“But because of the way our country is portrayed in the media, we have always been seen as the poor, the ones who don’t know this and that. Those people are missing the history of Haiti,” said Marie Paule Woodson, the assistant department director of human services for Miami-Dade County.

Woodson is alluding to the history of the Haitian Revolution, which resulted in the country’s claim to fame in 1804: the world’s first independent Black republic.

Miami-Dade county reaps the benefits of people like Woodson, the chair for the Haitian Women of Miami; Eveline Pierre, the founder of the Haitian Heritage Museum; Mecca aka Grimo, actor and spoken word artist; Chef Ken Sejour also known as Chef Creole; and Dr. Marie Flore Lindor-Latortue, candidate for Miami-Dade county school board. But, ironically, these talented individuals could never have reached the pinnacle of their success in Haiti.

For reasons ranging from unstable infrastructure, corrupt leadership, a mismanagement of funds and –most recently – a devastating earthquake in 2010, Haiti’s unemployment rate is at 40 percent and its literacy rate is a little less than 50 percent.

Suffice it to say, there are just not enough jobs to sustain the population of educated citizens, let alone the labor population.

So, people like Woodson – whose parents insisted she become a doctor – immigrated to Florida in 1982 to go to college.

“We couldn’t pursue our education over there because there was only one medical school and they could only accept 50 people at the time. I was smart but I wasn’t getting in. I also didn’t have a godfather – someone who works for the government – to pull strings, so there was no way I could continue my education.”

The first mass Haitian immigration to the U.S. in 1979 coincided with the Mariel boatlift of Cuba and another was in 1986 when the oppressive Duvalier dictatorship ended. After President Jean Bertrand Aristide was overthrown in 1991, there was another wave of immigrants to Miami.

Woodson’s father told her that he couldn’t leave her an inheritance when he died, but he could leave her education. Woodson and her brother could not stay in Haiti in order for her father to keep his promise. According to her, this sentiment is widespread among the Haitian people.

“My mother couldn’t read or write. My siblings and I taught her how when we got older. My father was the one with education and they both stressed: God, hard work, education and giving back,” said Woodson. “In fact, every Haitian parent wants you to be educated. Because our parents grow up so poor, they want better for their children. They don’t want us to repeat the cycle.”

For Haitians, Woodson says, education is the great equalizer; so, if it takes enrolling their children in private Catholic schools, paying for extra tutoring and sending them to the U.S. for more affordable college options, that’s what they’ll do, she said.

In fact, Woodson cites how prevalent colorism is in their culture, but that education neutralizes the effects. Haitians treat each other differently depending on if they have light or dark skin, she said.

“But if you are smart or you have education, you will be accepted by all. Even if you have dark skin,” she said.

Woodson received a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice and a master’s degree in public management with a specialization in public administration after immigrating, but it was not without her fair share of discrimination.

“I was working on my master’s at St. Thomas [University] when a fellow student asked me why I was getting a master’s degree. ‘You’re Haitian and a woman. Why are you here?’ He said he thought it was a waste of time. Guess what? A few years down the line, he and I were up for the same position. I’m sure he was surprised to see me,” she said.

The experience of being underestimated by other groups is somewhat monolithic to being a Haitian in South Florida.

Peterson Bonpied Jerome, who represented Haiti at the Under-17 level in South Florida in 1995, worked out with Haiti's senior national team in 2004 when they played Jamaica at the Orange Bowl and was skillful enough to be invited to train with Major League Soccer teams Miami Fusion and New York/New Jersey MetroStars, still gets underestimated on the soccer field to this day.

“People tend to associate the name of Haitian with not belonging. They prejudge us and don’t give us a chance to prove ourselves first. For example, Jamaicans don’t know I can play soccer as well as they can,” said Jerome. “When you step on the field, you become their equal, if you’re good. You become accepted.”

Jerome, who runs soccer programs for the city of Fort Lauderdale and is the founder of the Haiti Youth Development and Education (H.Y.D.E.) foundation, claims that soccer is a much bigger sport in Haiti than it is in Jamaica - an island that celebrates other sports like cricket and track and field.

Still, Jamaicans continue to downplay the skill of Haitian players in South Florida because they don’t trust the talent that comes from the country.

“We take pride in soccer and once Jamaican players see that, we become great friends,” said Jerome. “I believe soccer is a universal language.”

Jerome has literally put his money where his mouth is every year by self-financing HYDE’s Unification Cup involving Broward County teams who represent countries from around the world.

Jerome has literally put his money where his mouth is every year by self-financing HYDE’s Unification Cup involving Broward County teams who represent countries from around the world.

An annual tournament - comprising weekly matches and music concerts spanning two and a half months- has been his way of unifying diverse cultures around the game of soccer in South Florida.

“As Haitians, people think that we don’t do things with other ethnic groups. I want to go against that. If we want people to accept us, we need to show them that we can accept them. We don’t just wait for people to do things for us,” said Jerome.

Buffington “Tony” Barreau, the owner of AVD Photography in Davie, agrees that Haitians are open to receiving people of different cultures, even though those others may be reluctant at first.

He attended schools like Nautilus Middle, North Miami Middle and North Miami Senior High in the 1980s and 1990s and recalls how each school taught him something different about intercultural relations.

At Nautilus, a predominantly White and Jewish environment at the time, he was Black. Not Haitian, just Black. Even the African American students there sought solidarity with him.

At North Miami Middle, an influx of Haitian students began enrolling and Barreau started banding together with them to fight the African Americans.

“They were saying we eat cat but we all knew that we didn’t. There were more of us and we stood up for ourselves,” he said.

He even joined with some other Haitian students to form a deejay team called “LB” or Legume Boys.

“Legume is a Haitian food that’s a delicacy. Its’s something you can’t get all the time. It was good, tasty and special. That’s how we made a statement about us being Haitians,” he said.

At North Miami Senior, finally teeming with Haitian Americans and new Haitian immigrants in 1994, he was successfully out of the closet, but everything changed – though - when he found a point of connection with non-Haitian students.

“Growing up, I used to play the drums at church so I used to understand beats and rhythms. I was used to listening to Kompa and Zouk but then I heard reggae. I fell in love with it. It was a different version of the same Afro-Caribbean experience. I then began to understand conversations some of the Jamaicans would have at my high school,” he said.

He made friends with many of them and would spend time in their homes after school, realizing that they had far more in common than he originally thought.

“Our families raised us similar. You’re raised to know that your parents love you, but not to experience that they love you. Our dads are providers. They teach us how to be responsible without saying it. You just see it. I would see the same thing at my Jamaican friends’ house that I would see at my house,” said Barreau, whose dad was a taxi driver and had an import-export business.

A few years later, he met and married a Jamaican woman named Keesha and today she is the other half of his booming photography and visual design company.

“We get along great. We even cross-cook. We’ll have Haitian rice with Jamaican meat,” said Barreau.

Intercultural marriage is indeed a growing trend within the Haitian community in South Florida.

Woodson, who married an American man from Baltimore, said she was criticized for stealing one of the African American community’s eligible bachelors.

“I was working with a girl who told me ‘You came from Haiti and you got this nice Black American guy?’” she said.

Woodson also says she knows how important it is for her children to take pride in their Haitian heritage, especially because they bear an American last name.

“People always say to them, ‘I didn’t know you were Haitian’ and they have to know it’s nothing to be embarrassed about when people discover their heritage,” she said.

She is proud that her children speak Haitian-Creole and they love Haitian food. So does her husband.

Still, one major drawback in the Haitian community of South Florida is their economic power. According to a 2015 statistics by the Center for Immigration Studies, the share of Haitian immigrants and their young children (under 18) living in poverty in the U.S. is 20 percent.

Additionally, 46 percent of households headed by Haitian immigrants use at least one major welfare program, said the center.

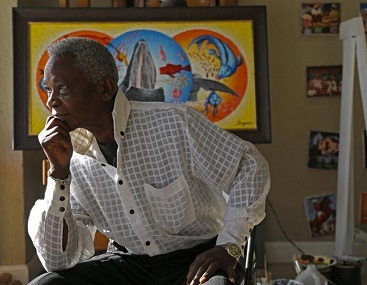

Joseph Wilfrid Daleus was a Haitian artist who worked in South Florida for 36 years before his death in December 2017. He claimed that most of his artwork could not be purchased by fellow Haitians.

Denzel Washington owns several of Daleus’ paintings and the Haitian consulate purchased a painting for $500,000. The highest price tag for one of his paintings has been $1 million.

Daleus, who worked mostly in oil and liquitex media, painted images of Haitian urban and rural life, Haitian rites of passage and Haitian vistas – images that many Haitians would love to own as a reminder of what they left behind.

Since the earthquake in 2010, the value of his work had increased because his paintings feature architecture of the capital city Port-au-Prince pre-2010. This hike in valuation made it even harder for Haitians in South Florida to support his art.

The Daleus gallery was located at 5910 Northeast Second Avenue in the Heart of Little Haiti and after his passing some speculated that it was gentrification that forced him to close his doors. This was only a few months before his death.

When Daleus was asked in 2016 about why his paintings go unappreciated by fellow Haitians, he said: “I’m so sad about the fact that my Haitian brothers cannot afford my work. No Haitians have Basquiat. That’s just like me. So many of my people don’t know my value. Normally, the people who buy my work are American, German, Canadian and Chinese people.”

Thus, from Little Haiti to South Beach, from Lauderhill to Miramar, from El Portal to North Miami, Haitians have infiltrated some of South Florida’s biggest urban centers and diverse industries.

“It’s such a melting pot here in Miami and we get to interact with so many cultures. We see ourselves as one people. Some people may treat you differently because you are Haitian but we have to learn to respect each other and we’d be a lot better off,” said Woodson.

Tiffani Knowles is the managing editor and founder of NEWD Magazine. Her hope is to become as "newd" as possible on a daily by embracing truth, authenticity and socio-spiritual awareness. She is bi-vocational as she is the owner of two businesses and a professor of Communication at Barry University in Miami, Florida. She is also the co-author of HOLA America: Guts, Grit, Grind and Further Traits in the Successful American Immigrant.

Tiffani Knowles is the managing editor and founder of NEWD Magazine. Her hope is to become as "newd" as possible on a daily by embracing truth, authenticity and socio-spiritual awareness. She is bi-vocational as she is the owner of two businesses and a professor of Communication at Barry University in Miami, Florida. She is also the co-author of HOLA America: Guts, Grit, Grind and Further Traits in the Successful American Immigrant.