The closer one gets to realizing a goal charged by fierce

creative expression and disinhibition, the closer one may get to losing touch

with reality.

The closer one gets to realizing a goal charged by fierce

creative expression and disinhibition, the closer one may get to losing touch

with reality.

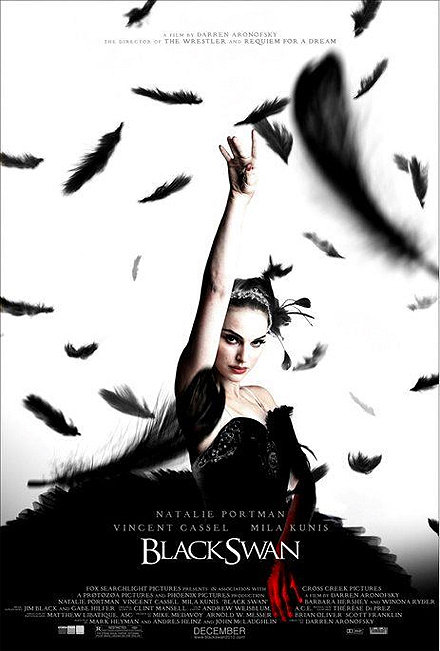

Alas, this phenomenon is real and true and plays itself out in the most decayingly beautiful manner since The Soloist. This season's Black Swan, directed by Darren Aronofsky, is frightening yet gives us a glimpse into the mind of an artist who knows that surrender is the only way to true perfection.

When a ballet dancer (Natalie Portman) wins the lead in

"Swan Lake," a most beautiful yet tragic ballet, she is perfect for

the role of the delicate White Swan, but has to push her life and mind to the

limits to pull out her character's flip side.

We closely follow this psychological thriller as it details

the story of Nina Sayers (Portman), a ballerina in a New York City ballet

company whose life, like all those in her profession, is completely consumed

with dance.

She lives with her retired ballerina mother Erica (Barbara

Hershey) who is zealously supportive of her daughter's professional ambition,

yet to a fault.

She lives with her retired ballerina mother Erica (Barbara

Hershey) who is zealously supportive of her daughter's professional ambition,

yet to a fault.

Nina is treated like the mechanical, porcelain ballerina who

twirls inside the confines of a box. While this is a place of comfort for her,

her talent is limited to her own "box" of exquisite form, flawless technique

and sweet grace.

When artistic director Thomas Leroy (Vincent Cassel) decides to replace prima ballerina Beth MacIntyre (Winona Ryder) for the opening production of their new season with Nina, the psychological battle ensues.

Swan Lake requires a dancer who can play both the White Swan

with innocence and grace, and the Black Swan, who represents guile and

sensuality. Nina is outshone by fellow company dancer Lily, (Mila Kunis) who

just happens to be the perfect personification of the Black Swan.

As the two young dancers expand their rivalry into a twisted friendship, Nina begins to get more in touch with her dark side with a recklessness that threatens to destroy her.

Giving into an old habit of self-mutilating and a new habit of full-on lesbian wet dreams, her "sweet girl" innocence slowly melts away, making room for the Black Swan - both on stage and in life.

Thus, should one surrender to the grueling requirements of

one's own artform (i.e. masturbation and a sexual encounter with one's teacher)

and still identify as one's self?

Thus, should one surrender to the grueling requirements of

one's own artform (i.e. masturbation and a sexual encounter with one's teacher)

and still identify as one's self?

It is common knowledge that artists, because of the innovative and expressive nature of their work, suffer from neurosis and emotional instability more than the average person.

It is my conviction that one must be grounded in something

more stable, more rock-like than oneself - the vacillating human.

In surrendering to the Black Swan, the only way Nina could have come out unscathed is if she had been locked into a divine force powerful enough to retrieve her, then stabilize her once again.